Partisan Division Has Reached Its Peak Shows An Alarming New Study That Identifies Three Crucial Components

Union workers caravan in support of Joe Biden.

- American political polarization has reached alarming heights, shows a new study.

- Democrats and Republicans hate the other side more than they love their own party.

- The polarization grows worse despite the fact that differences between the sides are not so dramatic.

To say that the current election is stressful and divisive is beyond an understatement. The United States is strained at the seams, ready to explode no matter who wins the presidency. A new study shows just how bad it’s become, with anger at the opposing party now outstripping the love a supporter might have for their own party. To put it in other words: People hate those on the opposite side of the political spectrum more than they care for their own.

Is this a recipe for disaster? The study describes the current political attitudes in the country as “political sectarianism,” linking it to religious fervor. The research also shows that, for many, political identity has become their primary identity.

The study’s lead author Eli Finkel, professor of social psychology at Northwestern University, described the dangers of the situation:

Finkel’s conclusions are based on a survey of dozens of published researched studies, going back to the 1970s. The research drew on the expertise of co-authors from six disciplines: political science, psychology, economics, sociology, management as well as computational social science.

1. “Othering” – seeing the other side as different.

Republicans And Democrats Hate The Other Side More Than They Love Their Own New Analysis Shows

Disdain for the opposing political party now outweighs affection for one’s own party, shows a new analysis by a multidisciplinary team of researchers.

Disdain for the opposing political party now outweighs affection for one’s own party, shows a new analysis by a multidisciplinary team of researchers. Its conclusions reveal for the first time on record that negative sentiment for the opposition outstrips positive feelings for one’s own partisan affiliation and may be more important than ideological differences in guiding political behavior.

The work, “Political Sectarianism in America,” appears in the latest issue of Science and provides a broad survey of current scientific literature to interpret the current state of politics.

The paper introduces the term “political sectarianism” to describe the phenomenon, offering a new framework to interpret the current state of politics and illuminate current scientific literature. Political sectarianism embodies religious fervor, such as sin, public shaming, and apostasy. But unlike traditional sectarianism, where political identity is secondary to religion, political identity is primary, the authors note.

The team includes researchers from several academic disciplines—political science, psychology, sociology, economics, management, and computational social science. Among them are New York University’s Jay Van Bavel, a professor of psychology and neural science, and Joshua A. Tucker, a professor of politics.

Study: Republicans And Democrats Hate The Other Side More Than They Love Their Own Side

“When ideals and policies matter less than dominating foes, government becomes dysfunctional,” researchers say

The bitter polarization between the Republican and Democratic parties in the U.S. has been on the rise since Newt Gingrich’s partisan combat against President Bill Clinton in the 1990s. But according to a new Northwestern University-led study, disdain for the opposing political party now — and for the first time on record — outweighs affection for one’s own party.

The study, titled “Political sectarianism in America,” will be published Oct. 30 by the journal Science. The authors provide a broad survey of current scientific literature to interpret the current state of politics.

The paper introduces the construct of “political sectarianism” to describe the phenomenon. Political sectarianism has the hallmarks of religious fervor, such as sin, public shaming and apostasy. But unlike traditional sectarianism, where political identity is secondary to religion, political identity is primary.

“The current state of political sectarianism produces prejudice, discrimination and cognitive distortion, undermining the ability of government to serve its core functions of representing the people and solving the nation’s problems,” said lead author Eli Finkel. “Along the way, it makes people increasingly willing to support candidates who undermine democracy and to favor violence in support of their political goals.”

Divided Nation: Democrats Republicans Hate The Other Side More Than They Love Their Own

“When ideals and policies matter less than dominating foes, government becomes dysfunctional,” researchers concluded.

— For the first time on record, disdain for the opposing political party outweighs affection for one’s own party, according to a new study published Thursday in the journal Science.

“When ideals and policies matter less than dominating foes, government becomes dysfunctional,” the study concluded.

“The current state of political sectarianism produces prejudice, discrimination and cognitive distortion, undermining the ability of government to serve its core functions of representing the people and solving the nation’s problems,” said lead author Eli Finkel. “Along the way, it makes people increasingly willing to support candidates who undermine democracy and to favor violence in support of their political goals.”

Finkel is a professor of social psychology with appointments at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and Kellogg School of Management. To ensure the study’s findings incorporated the collective knowledge base, he recruited co-authors from six academic disciplines: political science, psychology, sociology, economics, management and computational social science.

Using national survey data dating back to the 1970s, the authors combed dozens of published research studies to calculate “the difference between Americans’ warm feelings toward their fellow partisans and their cold feelings toward opposing partisans.”

The Divide Between Political Parties Feels Big Fortunately Its Smaller Than We Think

Image adapted from: Ben Sweet/Unsplash

Political polarization in the United States was once defined by ideological disagreement. Now, this ideological division has been fused with an “us versus them” sectarianism that feels reminiscent of divisiveness and vitriol more commonly seen in war-torn countries than in healthy democracies. To illustrate the current state of polarization in the United States, consider the following: in the lead up to the most recent presidential election, the federal government arrested a militia that allegedly planned to kidnap Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer, yard signs expressing support for both Democratic and Republican candidates were regularly stolen and vandalized, and businesses across the country boarded up their windows for fear of widespread post-election violence.

As social psychologists, we are interested in understanding how such a toxic form of polarization manifests in our everyday psychology, and how the mental models we hold can undermine social cohesion and democratic health. And as concerned citizens who are also scientists, we are also interested in identifying evidence-based solutions to overcome the division that defines American politics. Through a partnership between a research team at the University of Pennsylvania and the nonprofit organization Beyond Conflict, we work to translate research on political polarization into science-backed interventions to reduce conflict.

Why do these misperceptions matter?

How Americas Political System Creates Space For Republicans To Undermine Democracy

9) Republicans havean unpopular policy agenda

Let Them Eat Tweets

The Republican policy agenda is extremely unpopular. The chart here, taken from Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson’s recent book , compares the relative popularity of the two major legislative efforts of Trump’s first term — tax cuts and Obamacare repeal — to similar high-priority bills in years past. The contrast is striking: The GOP’s modern economic agenda is widely disliked even compared to unpopular bills of the past, a finding consistent with a lot of recent polling data.

Hacker and Pierson argue that this drives Republicans’ emphasis on culture war and anti-Democratic identity politics. This strategy, which they term “plutocratic populism,” allows the party’s super-wealthy backers to get their tax cuts while the base gets the partisan street fight they crave.

The GOP can do this because America’s political system is profoundly unrepresentative. The coalition it can assemble — overwhelmingly white Christian, heavily rural, and increasingly less educated — is a shrinking minority that has lost the popular vote in seven of the past eight presidential contests. But its voters are ideally positioned to give Republicans advantages in the Electoral College and the Senate, allowing the party to remain viable despite representing significantly fewer voters than the Democrats do.

10) Some of the most consequential Republican attacks on democracy happen at the state level

11) The national GOP has broken government

Mike Pence Accidentally Admits The Real Reason Republicans Hate Democrats So Much

The grassroots organization People for Bernie on Tuesday advised the Democratic Party to take a page from an unlikely source—right-wing Vice President Mike Pence—after Pence told a rally crowd in Florida that progressives and Democrats “want to make rich people poorer, and poor people more comfortable.”

“Good message,” tweeted the group, alerting the Democratic National Committee to adopt the vice president’s simple, straightforward description of how the party can prioritize working people over corporations and the rich.

Suggesting that a progressive approach to the economy will harm the country—despite the fact that other wealthy nations already invest heavily in making low- and middle-income “more comfortable” by taxing corporations and very high earners—Pence touted the Republicans’ aim to “cut taxes” and “roll back regulations.”

The vice president didn’t mention how the Trump administration’s 2017 tax cuts overwhelmingly benefited wealthy households and powerful corporations, with corporate income tax rates slashed from 35% to 21%, corporate tax revenues plummeting, and a surge in stock buybacks while workers saw “no discernible wage increase” according to a report released last year by the Economic Policy Institute and the Center for Popular Democracy.

Pence’s description of progressive goals was “exactly” correct, author and commentator Anand Giridharadas tweeted.

“Yes, and what’s wrong with making poor people more comfortable?” asked Rep. Ilhan Omar .

Think Republicans Are Disconnected From Reality It’s Even Worse Among Liberals

A new survey found Democrats live with less political diversity despite being more tolerant of it – with startling results

Last modified on Tue 8 Sep 2020 16.13 BST

In a surprising new national survey, members of each major American political party were asked what they imagined to be the beliefs held by members of the other. The survey asked Democrats: “How many Republicans believe that racism is still a problem in America today?” Democrats guessed 50%. It’s actually 79%. The survey asked Republicans how many Democrats believe “most police are bad people”. Republicans estimated half; it’s really 15%.

The survey, published by the thinktank More in Common as part of its Hidden Tribes of America project, was based on a sample of more than 2,000 people. One of the study’s findings: the wilder a person’s guess as to what the other party is thinking, the more likely they are to also personally disparage members of the opposite party as mean, selfish or bad. Not only do the two parties diverge on a great many issues, they also disagree on what they disagree on.

“This effect,” the report says, “is so strong that Democrats without a high school diploma are three times more accurate than those with a postgraduate degree.” And the more politically engaged a person is, the greater the distortion.

A coalition of college Republican clubs recently endorsed a tax on carbon pollution.

Republicans Dont Understand Democratsand Democrats Dont Understand Republicans

A new study shows Americans have little understanding of their political adversaries—and education doesn’t help.

About the author: Yascha Mounk is a contributing writer at The Atlantic, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins University, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and the founder of Persuasion.

Americans often lament the rise of “extreme partisanship,” but this is a poor description of political reality: Far from increasing, Americans’ attachment to their political parties has considerably weakened over the past years. Liberals no longer strongly identify with the Democratic Party and conservatives no longer strongly identify with the Republican Party.

What is corroding American politics is, specifically, negative partisanship: Although most liberals feel conflicted about the Democratic Party, they really hate the Republican Party. And even though most conservatives feel conflicted about the Republican Party, they really hate the Democratic Party.

America’s political divisions are driven by hatred of an out-group rather than love of the in-group. The question is: Why?

Democrats also estimated that four in 10 Republicans believe that “many Muslims are good Americans,” and that only half recognize that “racism still exists in America.” In reality, those figures were two-thirds and four in five.

Why Do We Suddenly Not Want Our Elected Officials To Get Along With Each Other

Surely the doxxing of an opponent’s donors, snarking on Twitter, and what basically amounts to little more than schoolyard name-calling is detracting and distracting from the job of good governance.

This is leadership? If all this bitter hatred is real, we’re really in trouble. People who hate each other this much can’t be expected to overcome such disfunction. If it’s exaggerated for effect, or more specifically for campaign fundraising effect, we’re in even worse trouble.

Because people are actually buying it.

If their elected official is blasting, ripping, sick-burning, and raging against “evil” political opponents on Twitter, that elected official is doing what we elected them to do. Get them!

If the elected official is reaching across the aisle, compromising, and working together with their political opponents, they are NOT doing what we elected them to do. Get them!

Except they are. That is exactly what elected officials were sent to Capitol Hill to do; bipartisan compromise is the only way anything ever gets done.

What would become of a company whose employees treated each other this rudely, and in public?

Like any business, colleagues have to work together. That means respecting each other, on and off social media; even if you don’t like each other.

Who are we kidding, especially if you don’t particularly like each other.

Or not.

Different strokes.

Getting along has never been more important. So do us all a favor, and tone it down, whatever your political bent.

Pandemic Puts A Crimp On Voter Registration Potentially Altering Electorate

For all the discussion about the effect of voter ID laws, however, a study last year found that whatever impact those laws might have is offset by increased organization and activism by nonwhite voters — leading to no change in registration or turnout.

Another battleground is early and absentee voting. Rules vary by state, with some requiring more explanation than others as to what’s permissible.

Bitter lessons

The parties today have arrived at this moment after years of what they would argue were bad experiences with elections at the hands of their opponents.

Republicans, among other things, sometimes point to what they believe was cheating in the 1960 presidential race. Alleged Democratic chicanery, in this telling, threw the results to John F. Kennedy and cost the race for Richard Nixon.

Fraudulent IDs, undocumented immigrants voting, people being “bused in” on Election Day remain consistent themes when Republicans talk about elections.

Democrats look to the decades of Jim Crow discrimination that kept many black voters out of elections.

More recently, they look at the Supreme Court’s 2000 decision that handed the outcome of that election to George W. Bush over Al Gore. The court halted the counting of ballots that Democrats argued could have changed Florida’s results, swinging the state to Gore.

Abrams’ group perceives what it calls a deliberate campaign by the establishment to purge Georgia voter rolls of mainly black or Democratic voters.

Matters of principle

We’re Less Far Apart Politically Than We Think Why Can’t We All Get Along

Partisans on both sides of the aisle significantly overestimate the extent of extremism in the opposing party. The more partisan the thinker, the more distorted the other side appears. And when we see the opposition as extremists, we fear them. Our tribal thinking prepares us for battle.

What’s the solution? More information? More political engagement? More education?

Surely more information leads to better judgment. But social scientists at the international initiative More in Common find that having more information from the news media is associated with a less accurate understanding of political opponents. Part of the problem appears to be the political biases of media sources themselves. Of all the various news media examined, only the traditional TV networks, ABC, NBC, and CBS, are associated with a better understanding of political views.

This discrepancy may be a result of the lack of political diversity among professors and administrators on campus. As political scientist Sam Abrams found, the average left to right ratio of professors nationwide is 6 to 1 and the ratio of student-facing administrators is 12 to 1. Democrats who have few or no Republican friends see the other side as more extreme than do those with more politically diverse friends. And the more educated Democrats are, the less likely they are to have friends who don’t share their political beliefs.

So what can you do?

A version of this article appeared on the Newsmax platform.

Most Republicans See Democrats Not As Political Opponents But As Enemies

The idea is a simple one: A country in which people with at-times differing views of how things should be run get together and vote on representatives who will enact policy. The candidates with the most support take office, working to build consensus for the policies their constituents want to see. Both before and after the election, there’s an expectation that disagreements will be resolvable and resolved.

This is an idealized version of our system, of course, but that’s how ideals work. Central to American politics is the idea that even if your candidate loses, the winner will advocate for you. But in an era in which the winners of elections in November are often those who manage to clamber over their primary opponents in the spring, the idea that a Democratic legislator will feel beholden to Republican constituents — or vice versa — seems almost quaint.

That said, we run the risk of establishing an equivalence where one may not exist. For example, we have new polling from CBS News, conducted by YouGov, which explores how members of each political party tend to think of members of the opposing party.

Most Democrats say that they tend to view Republicans as political opponents. Most Republicans say that they tend to view Democrats as enemies.

How is this unwound?

The Legal Fight Over Voting Rights During The Pandemic Is Getting Hotter

Or as former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican, told NPR, there are no “fair” maps in the discussion about how to draw voting districts — because what Democrats call “fair” maps are those, he believes, that favor them.

No, say voting rights groups and many Democrats — the only “fair” way to conduct an election is to admit as many voters as possible. Georgia Democrat Stacey Abrams, who has charged authorities in her home state with suppressing turnout, named her public interest group Fair Fight Action.

Access vs. security

The pandemic has added another layer of complexity with the new emphasis it has put on voting by mail. President Trump says he opposes expanding voting by mail, and his allies, including White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany, call the process rife with opportunities for fraud.

Even so, Trump and McEnany both voted by mail this year in Florida, and Republican officials across the country have encouraged voting by mail.

Democrats, who have made election security and voting access a big part of their political brand for several years, argue that the pandemic might discourage people from going to old-fashioned polling sites.

Democrats And Republicans Dislike Each Other Far Less Than Most Believe

A new study indicates that some of our political polarization is based on unfounded beliefs.

- Democrats and Republicans dislike and dehumanize one another roughly equally.

- At least 70% of both Republicans and Democrats overestimated how much the other group disliked and dehumanized their group.

Political polarization is a well-documented issue in the United States, and the schism between left and right can sometimes feel impossible to overcome. But a new study from the Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab at the Annenberg School for Communication and Beyond Conflict may offer some hope for the future.

Often, people’s actions towards a group they are not part of are motivated not only by their perceptions of that group, but also by how they think that group perceives them. In the case of American politics, this means that the way Democrats act toward Republicans isn’t just a result of what they think of Republicans but also of what they think Republicans think of Democrats, and vice versa.

The study, , found that Democrats do not dislike or dehumanize Republicans as much as Republicans think they do, and Republicans do not dislike or dehumanize Democrats as much as Democrats think they do. This finding could indicate that some of our political polarization is based on unfounded beliefs.

They Hate Each Other’s Political Views So Why Have They Become Friends

Our political culture is becoming more and more polarized. In such a partisan world, can we still get along with those whose beliefs we can’t abide?

Last modified on Thu 8 Oct 2020 11.33 BST

When Glenn Stanton and Sheila Kloefkorn first ended up in the same room together, they knew they were not going to see eye to eye.

Stanton, the director of Global Family Formation Studies at Focus on the Family, an evangelical Christian values organization, had spent years vociferously fighting gay marriage.

Kloefkorn, on the other hand, had married her wife in 2014, on the day gay marriage became legal in Arizona. Having fought for equal marriage for decades, finally being able to wed meant letting go of a life’s share of feeling like a second class citizen.

But today, Stanton and Kloefkorn are friends. They met through Braver Angels, an organization which encourages people to befriend and understand people who have differing political opinions. Today, they laugh when people are surprised at their friendship.

“I don’t believe that Glenn is out to get me in the way I probably would have in the beginning of my activism. I just really believe he feels strongly about the things he cares about, and that’s a great thing,” says Kloefkorn.

Reaching to the other side may sound like self-inflected pain, butKloefkorn took those steps for a very personal reason: she the only liberal in her staunchly conservative, evangelical family.

New Poll: Americans Overwhelmingly Support Voting By Mail Amid Pandemic

Traditionally, Republicans have tended to support higher barriers to voting and often focus on voter identification and security to protect against fraud. All the same, about half of GOP voters back expanding vote by mail in light of the pandemic.

Democrats tend to support lowering barriers and focus on making access for voters easier, with a view to encouraging engagement. They support expanding votes via mail too.

The next fight, in many cases, is about who and how many get what access via mail.

All this also creates a dynamic in which many political practitioners can’t envision a neutral compromise, because no matter what philosophy a state adopts, it’s perceived as zero-sum.

Why Hatred And Othering Of Political Foes Has Spiked To Extreme Levels

The new political polarization casts rivals as alien, unlikable and morally contemptible

In 1950 the American Political Science Association issued a report expressing concern that Americans exhibited an insufficient degree of political polarization. What a difference a new millennium makes. As we approach 2020’s Election Day, the U.S. political landscape has become a Grand Canyon separating blue and red Americans.

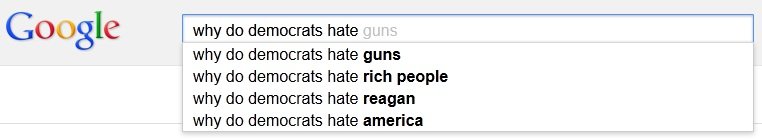

So why is this happening? In a review of studies published today in the journal Science, 15 prominent researchers from across the country characterize a new type of polarization that has gripped the U.S. This phenomenon differs from the familiar divergence each party holds on policy issues related to the economy, foreign policy and the role of social safety nets. Instead it centers on members of one party holding a basic abhorrence for their opponents—an “othering” in which a group conceives of its rivals as wholly alien in every way. This toxic form of polarization has fundamentally altered political discourse, public civility and even the way politicians govern. It can be captured in Republicans’ admiration for Donald Trump’s ability to taunt and “dominate” liberals—distilled to the expression “own the libs.”

Scientific American delved into these issues with Eli J. Finkel, a psychology professor at Northwestern University and lead author of the new Science paper.

But how do you get people those facts? How do you get them to even come to the table and listen?

Much Of Ohio Is Trump Country And That Complicates Things For The Gop

However, he said, “conservatives, since the 1960s, have increasingly defined American society as a colorblind society, in the sense that maybe there were some problems in the past but American society corrected itself and now we have these laws and institutions that are meritocratic and anybody, regardless of race, can achieve the American dream.”

Confronted by the Black Lives Matter protests of last summer, as well as the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 curriculum, which roots American history in its racist past, Hartman said many Americans want simple answers.

“And so critical race theory becomes a stand-in for this larger anxiety about people being upset about persistent racism,” he said.

Legislative action

States such as Idaho and Oklahoma have adopted laws that limit how public school teachers can talk about race in the classroom, and Republican legislatures in nearly half a dozen states have advanced similar bills that target teachings that some educators say they don’t teach anyway.

There’s movement on the national level too.

Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., has introduced the Combating Racist Training in the Military Act, a bill that would prohibit the armed forces and academics at the Defense Department from promoting “anti-American and racist theories,” which, according to the bill’s text, includes critical race theory.

toggle caption

Donalds said the country’s history, including its ills, should be taught, but that critical race theory causes more problems than solutions.

Why Cant Democrats And Republicans Agree On Almost Anything Anymore

Why We’re Polarized

Early on in his newly released Why We’re Polarized, Vox cofounder Ezra Klein explains that his book is not meant to guide us out of the morass that is American politics. Instead, he hopes to deliver a helicopter view showing us how we got so deep in, to view from above the system driving us all batty.

“What I am trying to develop here isn’t so much an answer for the problems of American politics as a framework for understanding them,” Klein, a self-acknowledged liberal, writes in his introduction. “If I’ve done my job well, this book will offer a model that helps make sense of an era in American politics that can seem senseless.”

For Klein, that making sense can only begin if you accept that where we are today in terms of partisanship is fundamentally different from where we’ve been in the past. “The first thing I need to do is convince you something has changed,” he writes. What has changed, exactly, is that “the Democratic and Republican parties of today are not like the Democratic and Republican parties of yesteryear.” Namely, in the past, being a Republican or a Democrat was “not a rich signifier of principles and perspectives.”

Why this realignment happened is complicated—and much of it has to do with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the split it caused in the Democratic Party between Northern liberals and Southern conservative Dixiecrats.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

A Century After The Race Massacre Tulsa Confronts Its Bloody Past

Academics, particularly legal scholars, have studied critical race theory for decades. But its main entry into the partisan fray came in 2020, when former President Donald Trump signed an executive order banning federal contractors from conducting certain racial sensitivity trainings. It was challenged in court, and President Biden rescinded the order the day he took office.

Since then, the issue has taken hold as a rallying cry among some Republican lawmakers who argue the approach unfairly forces students to consider race and racism.

“A stand-in for this larger anxiety”

Andrew Hartman, a history professor at Illinois State University, described the battle over critical race theory as typical of the culture wars, where “the issue itself is not always the thing driving the controversy.”

“I’m not really sure that the conservatives right now know what it is or know its history,” said Hartman, author of A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars.

He said critical race theory posits that racism is endemic to American society through history and that, consequently, Americans have to think about institutions like the justice system or schools through the perspective of race and racism.

Why Democrats Hate The Electoral College And Republicans Love It

Funny thing. Democrats, who keep losing elections where they get more votes, want to get rid of the Electoral College and Republicans, who keep winning elections where they get less votes, want to keep it.

The Electoral College is certainly the weirdest part of American democracy; a confusing system with a troubled history and an ugly past.

Here are some questions you might have wanted to ask:

1. Why are people talking about the Electoral College right now? A Democrat running for President, Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, said at a recent CNN town hall should be abolished.

“Well, my view is that every vote matters,” Warren said. “And the way we can make that happen is that we can have national voting. And that means get rid of the Electoral College and everybody counts.”

Plus, 11 states and the District of Columbia have joined something called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, whereby states would simply agree to pledge their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner. Colorado became the 12th state to join that effort last week and Delaware and New Mexico may be next.

However, the compact will only go into effect if a majority of electoral votes are pledged to the popular vote. With Colorado, they’ve only got 181 electoral votes.

9. How are the 538 electoral votes assigned? Each state gets at least 3 electors. California, the most populous state, has 53 congressmen and two senators, so they get 55 electoral votes.